Coral Disease and Diversity in Barbados

- myrahgraham

- Aug 15, 2019

- 11 min read

Updated: Aug 17, 2025

Holetown, Barbados

ABSTRACT: Coral reefs currently face an increase in disease epidemics, further putting reef ecosystems in decline. Protective measures in the form of policy and MPAs are now trying to protect reefs and buffer against the effects of environmental degradation. By protecting reefs, it is thought that higher coral diversity will impede pathogen progression in the long term. However, high host density may allow certain pathogens to progress faster. Underwater surveys were conducted over the span of 1 month, in Barbados. Four reefs (including 1 MPA) were surveyed to observe whether reefs with higher host density and lower coral diversity had higher instances of YBD. The MPA only showed a significant difference in host density compared to the other reefs, yet still had similar amounts of YBD and coral diversity. These results indicate that other factors and their interactions may be responsible for instances of YBD on boulder coral in Barbados. The MPA was not a limiting factor to coral disease, prompting the need for further analysis on effective tools to manage reef epidemics. It will be important for policy makers to adapt legislation in order to keep these crucial organisms from complete deterioration.

KEYWORDS: community ecology, coral disease, Caribbean, Yellow Band Disease

Introduction

Corals are important animals. Considered to be "the foundation species of tropical coral reef ecosystems", corals create a physical structure and complex community from which thousands of other species depend on (Bruno et al. 2007). In essence, coral reefs are oases for biota in relatively inhospitable oceans. However, this hub of marine life is currently under threat from many natural, environmental and anthropogenic factors. This is especially critical for major reef-building corals in the boulder category, namely the Montastraea genus (Weil et al. 2009). Indeed, it is estimated that "nearly one-third of reef-building corals face elevated extinction risk" (Sokolow, 2009). With increasing stress on

corals, disease is now the most destructive influence on corals worldwide (Raymundo et al. 2009). This is particularly significant in the Caribbean, where "over 70% of all coral disease reports" have led to the region being labeled as a disease "hot spot" (CDWG 2007; Harvell et al. 2004). Furthermore, epidemics come in waves which can sometimes cause up to 95% mortality for important reef-building corals in the area (Weil et al. 2009). The dynamics of these contagions depend on the host/pathogen relationships and environmental conditions. Since most corals can only tolerate temperatures of 18-30°C, increasing ocean temperatures with climate change are expected to further stress the corals (Harvell et al. 2004). Temperature is also an important factor for disease prevalence, with "most outbreaks [occurring] during the warmest season of the year" (CDWG 2007). Expected impacts involve the weakening of coral health, along with an increase in the virulence of coral pathogens (Sokolow, 2009). For boulder corals,

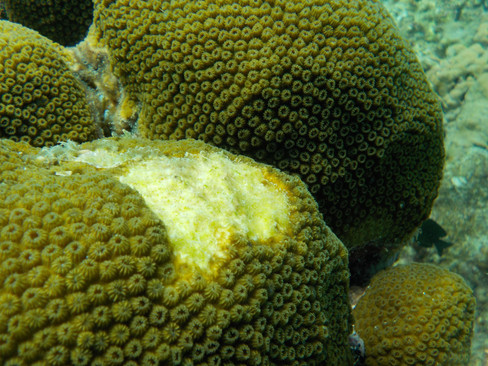

this means a potential onslaught from the 7 known biotic diseases known to infect their colonies (Weil et al. 2009). Of these, Yellow Band Disease (YBD) is the most identifiable to boulder colonies. Much like the name entails, YBD is a pathogen that produces a yellow band of infected polyps, which progresses across the colony as polyps die and leave behind exposed calcium carbonate skeleton (Fig.2). Because corals derive 80% of their energy from photosynthesis, the destruction of the photosynthetic polyps implies that the entire host organism is weakened the further the infection progresses (Weil et al.

2009). These consequences lower reef coral density and diversity, which is thought to reduce the ecosystem resilience (Raymundo et al. 2009). Since the Montastraea spp. are the largest and most abundant coral species in the Caribbean, their decline could lead to a widespread community population phase shift (Weil et al. 2009). Conversely, this could lead to other coral species filling this niche. However, current declines in most coral species make it more likely that other biota such as algae will colonize the boulder-sized spaces (Fung et al. 2011).

As the scales tip, humans will also find themselves thrown off balance. Fisheries, dive tourism and coastal protection in the Caribbean will all experience rapid decline with coral reef deterioration. This translates into estimated yearly losses of USD$580-860 million over the next 50 years (Schumann et al. 2013). The majority of this loss will be felt by the 1 billion people directly dependent on reef products (Harvey 2017). Barbados is one such vulnerable nation, particularly because of its 92km² of nearshore reefs relative to its 97km of coastline (Schuhmann et al. 2013). The island's south-eastern location also places the reefs in a precarious location, given that “disease prevalence increases from north to south in the Caribbean" (CDWG 2007). This was reflected in the severely degraded state of 80% of Barbados' fringing reefs in 2007 (Mycoo, 2013). The substantial importance of reefs in Barbados has prompted policy makers and environmentalists to legislate protective measures. As of 2001, 2.2km² of fringing reef

became protected under the National Conservation Commission (NCC) (Mahon and Mascia, 2003). The designation of protected area allowed for the prohibition of fishing and other commercial activities damaging to reefs. The Folkestone Marine Protected Area (MPA) is tasked with conserving fish diversity, (and by extension corals), in order to promote reef ecosystem resilience. It is projected that the MPA will demonstrate a difference in coral diversity and boulder density due to its protected status. Therefore, it will serve as the control site to answer the question: Does coral composition and cover

buffer against disease? Because of host/pathogen dynamics, one would expect a more diverse reef with a lower density of the host boulder coral to have less YBD present.

Methods

To test this hypothesis, the MPA will be compared to 3 other reefs that do not benefit from protected status. A pilot study was done to know which coral species and related pathogens were most present in the area. Yellow Band Disease (YBD) was most constant across all sites, with its host the boulder coral being the most abundant. Therefore, this pathogenic interaction was chosen for further research. In this study, boulder corals are considered to be all Montastrea spp. complex species found around Barbados.

Other coral groups included starlet coral (Siderastrea spp.), golf coral (Favia fragum), fire coral (Millepora complanata), finger coral (Porites furcata, Madracis auretenra) and brain coral (Diploria spp.) Human and Deloach). YBD was identified in the field using the visual cues outlined in the Coral Disease Identification Handbook. Disease was taken as the counts of YBD infecting a boulder coral outcrop per transect (Bruno et al. 2007; Raymundo et al. 2009). Coral diversity was sampled by the count of coral

species groups per transect. The coral density was sampled using the line intercept method (Raymundo et al. 2009). The area of study was along 3.87km of the west coast, where the four reefs (MPA, 1N, 1S, 2S) were surveyed. Using Google Earth Pro, reefs were chosen to the North (N) and South (S) of this reference reef based on their similarity in size and depth to the MPA. (Fig. 1).

Over the course of a month, snorkeling surveys were done to collect the data. Four 20m x 2m transect belts were randomly placed parallel to the reef crest at each reef (Page et al. 2009). An acclimatization period of 10 minutes was used before beginning the surveys (BIOL334). Surveys began with a timed swim of 5 minutes, starting from the weight to the transect reel. Any instances of YBD were recorded on a PVC slate, as well as photographic records taken using a Nikon Coolpix underwater camera (Fig. 2).

Following this, a timed 15 minute swim was done from reel to weight. A count of all coral species within the 40m² area, as well as recording on the slate all intercepting species and their widths was done in this time. All data was then transferred online and SPSS was used to run parametric tests for the analysis.

Gif 2: Transect 2 and 15

Results

YBD infections were found at all reefs and counted in each transect. Differences in YBD concentrations, overall coral diversity and boulder coral density were statistically evaluated using a 2-way type I ANOVA. This was done across reefs and MPA vs. non-MPA sites using transect values averaged per reef. Only those results at a significance value above α=0.05 were retained. YBD concentrations were taken as the counts of YBD divided by the counts of boulder coral on a given transect. Instances of YBD

concentrations varied across reefs, including the MPA (p<0.016, F=5.978). YBD concentrations ranged from 2.6% in the 1N reef to 61.2% at the 2S reef (Fig. 3). Therefore, the MPA was not a factor in whether or not one would expect YBD infections on a reef.

Coral cover for all recorded species (boulder, starlet, golf, fire, finger and brain) varied in relative compositions across reefs (p<0.018, F=5.753). Coral cover was taken as a percentage of a given coral species per transect and averaged at the reef level (Fig. 4). The highest coral cover was found on reef 2S, which also had the highest YBD concentrations per reef (Fig. 3 &5). No difference was found between MPA or non-MPA sites for either dependent variables. In other words, the MPA was did not have more

or less coral diversity than other reefs along the coast.

Percent boulder coral was considered in the same way as percent coral cover (Fig. 5). Boulder coral density was not found to differ across reefs, but a significant difference in concentrations was found between MPA and non-MPA sites (p<0.025, F=38.811). Percent boulder coral cover was 12.81% for the MPA, and 24.94% on average for all non-MPA sites (Fig. 6). The relatively lower average boulder cover in the MPA is therefore an important consideration, because this means the YBD host density was lower. At the reef level, the significant difference in instances of YBD and overall coral diversity leads to

less emphasis on MPA status, and more towards other reef-level factors.

Discussion

Corals are clones. Each boulder head is a clone of its predecessor, making large colonies

impressively singular. In the face of an epidemic, it can lead to eradication of the host. This is because of "their genetic homogeneity, coupled with the relatively rapid evolution of pathogens compared to hosts" (Harvell et al. 2004). The evolution of the pathogen is known as virulence, with a fast evolution translating as high virulence. For YBD, the virulence of the suspected Vibrio bacterium varies from a few mm-cm per month (Weil et al. 2009). However, caution is needed before applying epidemiological models in aquatic settings. Not only is it unclear how transmission happens underwater, but the

immune systems of corals are so vastly different from our own, that our current models fail to predict the progression of contagion (Harvell et al. 2004). The notion of vectors is especially relevant for YBD, as it was demonstrated that infection is not spread through direct contact or through the water column (Weil et al. 2009). This experimental evidence points to a mobile mode of transmission other than the pathogen itself; a vector is very likely. Although not much is known about YBD vectors (Harvell et al. 2004, Raymundo et al. 2008), it was found that "corallivorous fishes feed preferentially on physically damaged, stressed or diseased coral tissue, and increase the rate at which disease spreads" on a reef (Raymundo et al. 2009). Further research should compare bacterial cultures in fish to those found on infected coral heads. One challenge with this approach is the relative difficulty in isolating the responsible bacterium, protozoa or fungi (Rosenberg 2004). This is because the surface layer of corals naturally hosts a dynamic and complex community of microorganisms (Rosenberg 2004). Making matters more complicated, temperature was found to correlate to differences in surface-layer

microorganism assemblages, and subsequently YBD prevalence (Sokolow 2009). Another link was found suggesting a relationship between human presence and coral disease. This relationship is likely as a result of nutrient loading and destructive coastal activities such as tourism and fishing (Costal et al. 2000, CDWG 2007).

For the surveyed reefs in Barbados, instances of YBD were counter to initial assumptions. As seen in Figures 3 & 6, reefs with low host density had high amounts of YBD. These results are surprising, because high host densities are normally a factor influencing the extent to which the pathogen can spread (Page et al. 2009). For example, it was expected that higher host cover would increase the likelihood of transmission from a diseased coral to a healthy one (Bruno et al. 2007). Although overall coral cover was high where there were high counts of YBD, it remains unclear how these two factors

could be linked (Fig 5). In the boundaries of an MPA, it was expected that there would be high boulder coral density due to the unimpeded growth allowed by the protection from human activity. In reality, the MPA had a significantly lower concentrations of the host coral compared to the other reefs. The much lower host density runs counter to classic epidemiological models, where "[a] positive relationship between host density and disease prevalence" was shown (Bruno et al. 2007). Indeed, the MPA showed

an almost 50% reduction in boulder coral density compared to the average of non-MPA reefs, yet showed no difference in YBD prevalence (Fig.3 &6). In other words, low Montastraea density was not observed in conjunction with a difference in YBD prevalence. This could either indicate that the vibrio bacterium is not infectious, is not easily transmitted by direct contact or originates in another vector species (Bruno et al. 2007). It could also indicate the YBD is not solely limited by host density, as was seen in the MPA (Harvell et al. 2004). This last claim is supported by evidence found in Puerto Rico, where the interaction between temperature and host density were more likely to determine YBD instances (Page et al. 2009; Sokolow 2009). Furthermore, it was found that contamination was not the only way in which YBD was transmitted in the Caribbean (Sokolow 2009).

Coral diversity was another factor expected to regulate instances of YBD. It was found that regardless of a reef's protected status, differences in the coral diversity can occur alongside differences in disease prevalence; the Folkestone MPA did not show any difference in instances of YBD compared to other nearby reefs. When looking at the reefs overall, reef 2S exhibited the highest coral cover, and subsequently the highest YBD abundance (Fig 3 &5). Reef 2S also had the most equal distribution of coral groups across the reef, possibly as a result of lower abundance in the usually dominant boulder

coral (Fig 4 &6). The high diversity and overall coral cover, observed alongside high instances of YBD lead to the possible notion that reef diversity is not enough to buffer against coral disease. Furthermore, the fact that the MPA showed no significant difference in diversity or YBD prevalence demonstrates that the protected status of the reef may not be enough to ensure its resilience. However, the data from this study is but a brief snapshot of the ecology of these reefs. Disease progression is now understood to be non-linear, with cycles of infection broken by host die-offs, and renewed when new territory can be colonized (Rosenberg et al. 2007). In other words, the ebb and flow of disease "rises as pathogens spread among susceptible hosts and then falls as infected hosts are removed by death or recovery" (Sokolow 2009). The results found in May-June of 2018 may be but a brief glimpse at the dynamics of YBD on local reefs.

Longer term observations would be more appropriate to inform public policy. Tasked with protecting coastal waters, the Coastal Zone Management Unit (CZMU) has been in operation since 1998 (Mycoo 2014). Their legislative plan is called the Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM), and mandates the limiting of development impacts on coastal waters, and therefore coral reefs. Setbacks are the most crucial tool outlined in this plan, which requires all buildings to be at least 30m from the high water line (Mycoo 2014). With tourism being the most important part of Barbados' economy, this is

a crucial law limiting beach encroachment by the hotel and tourism industry (Mahon 2003). This is especially important since recreational divers listed the amount of live coral and biodiversity on a reef as top priorities in their choice to visit the island (Schuhmann et al. 2013). Thus, the importance of healthy reefs doesn't just provide ecosystem services, but socio-economic services as well. However, public policy in Barbados has not fully protected the reefs yet, as seen by the high abundance of YBD on the west coast.

Conclusion

Host density, coral reef diversity and policy have a more complex relationship to coral disease than previously hypothesized. There was no directly observable link between the density, diversity and disease prevalence of a reef. Rather, it is probably interactions with other factors outside the scope of this study which enhanced the likelihood of YBD infections. Factors such as temperature, nutrient loading, human activity and vector presence were likely involved (CDWG 2007; Bruno et al. 2009).

Comments